Space Industry Analysis: Like a Circle in a Spiral

Like a starship that’s launching, running rings around the moon, research and analysis are more about judgment and interpretation than facts. But facts help.

This post is going to be a little different. It’s about space industry analysis. It’s not an analysis of the space industry. Instead, I attempt to describe some of my processes behind the analysis. And, to be clear, this isn’t a step-by-step manual for what I do, but a description of some of my actions and the rationales behind them. For those readers interested in the latest space industry guesses, this is their chance to step off.

I’ve been wanting to write something like this for months. I don’t know if readers will find it tedious or interesting, especially since it’s about my process. I can’t know until I write and post this article. I do know that readers can be a fickle lot. That is not a criticism of readers, by the way–just the nature of working on the web. Readers are awesome!

Much of my work involves judgment and gathering information on space industry businesses, activities, and technologies. It helps that my personality is suited to this kind of research. I’m stubborn, skeptical, love reading, curious, thoughtful, introverted, and resourceful. I obviously enjoy writing (perhaps a bit too much). I know that as I sort through the information, my mind works on it simultaneously in the background.

Sources: The Circles that I Find

I am also quite the data-provenance snob because analyses and forecasts based on dubious data sources lead to questionable results and conclusions. I’ve mentioned the problem of irrelevant or non-credible sources before and their tendency to propagate thanks to the way certain search algorithms work. Even excellent data sources generate many questions, but dubious data makes defending and justifying observations much more tenuous. If I initially find data with a questionable source, I’ll highlight it and eventually find a better source.

That all explains why I generally seek and mostly find primary sources for launch vehicle (and spacecraft) data. Most of the time, finding the sources I need is relatively easy. SpaceX, for example, posts mass information about its rockets on its website.

Others, such as ULA or the China Academy of Launch Vehicle Technology, do as well. And if that information isn’t on their sites, it’s usually in their user manuals. I must assume that what these companies advertise to potential customers as capabilities is true. On the other hand, a Chollima-1 (from North Korea) requires more digging. A system like that might prompt me to seek out different sources.

I will resort to looking through secondary data sources when I must and Wikipedia and TED speeches when I’m desperate. To be fair, I usually go to Wikipedia to follow links to primary sources when they are available (they often aren’t). For those wondering about the distinction among data sources, please go to this site. The tendency for several research and news organizations to rely on unverified or unreliable data sources is an entirely different discussion.

Tools: Tunnels that I Follow To Tunnels of Their Own

Those data sources tend to lead to other sources, and I sometimes follow the data rabbit hole and inevitable branches. I use as many tools as possible to help with data searching, including Google and Microsoft Translate. Those are extremely useful for scouring sites from China, Russia, Japan, and India. I rely on them because I’ve noticed that while some host English versions of their sites, they usually don’t update or even include the same information that appears on their local language sites.

That fact, by the way, is not implying anything nefarious. After all, why wouldn’t the local language version have more comprehensive information? That’s the language they know, and they usually cater to the customers from their nations. Organizations from European nations do this, as do ones from the Middle East.

Most U.S. companies, on the other hand, have the luxury of not even thinking about dual-language sites for their business. Imagine trying to maintain two exact versions of a website in two languages. That’s nightmarish. This is why it’s puzzling but commendable that many Chinese space organizations and companies appear to have English versions of their sites.

Other tools are browsers and search engines (and vocabulary–word choice matters when searching). I don’t trust or rely on Google to get what I want. Brave is my default browser, and its default search engine often puts information in front of me that Google somehow misses. But when I can’t find it on Brave, it’s Bing or Google. I’ve also dabbled in Microsoft Copilot and have been sorely tempted to try the Arc browser. Anything that helps get the data I want quickly is valuable, instead of wasting time sorting through the results of what a search engine “thinks” I want (such as ads or irrelevant data).

So, the web is critical for me as I search for all sorts of data. Sometimes, I’ll reach out to people, but more often than not, I can find what I’m looking for from primary sources all over the web. It also helps to be “stupidly stubborn” - an endearing term my spouse has used to describe me occasionally. Government Accountability Office and agency budget reports, technical papers, databases, etc., require digging and patience and eventually become helpful sources.

At this point, it’s probably healthy for me to admit that my interest in those sources “ain’t right.” But I can stop when I want, so it’s not a problem, right? Right?

Judgment: Words that Jangle In My Head

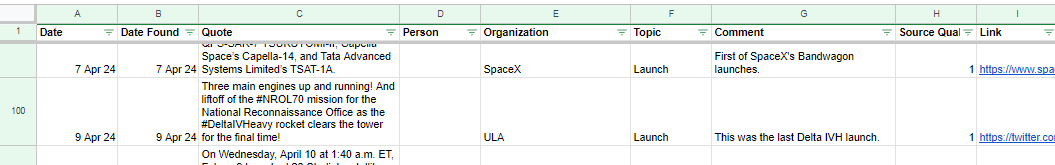

All the useful information I find gets entered into a spreadsheet–even source links and comments (as in the figure below).

That means that I have already determined (that whole judgment thing) what facts I am gathering that will be relevant or useful to readers. That’s part of the battle for a researcher–what data to collect. There’s a tendency to collect ALL THE DATA, but then what? A rocket’s dimensions and serial numbers are data–but are they relevant and interesting? It’s all a judgment call, but some calls are less risky.

The insidiousness of getting more data is a tendency to play with it more. As I said before, my mind is working with the information in the background. But collecting all the data and then presenting every bit of it to readers isn’t a great use of anyone’s time. I’d argue there’s little value in doing that. But divining stories, trend observations, and anything else not obvious from that data is a creative and usually more interesting role. It also depends on what data is being analyzed.

Rocket dimensions and serial numbers might be pertinent to CAD artists or customers, but I suggest that they are not interesting to most readers–at all (even with reuse). Ditto for the time of a launch (aside from determining UTC and orbits). Even stories about launch vehicle upmass are pushing many readers’ interest boundaries. However, the type of payload a rocket launches, who launched it, whether it was successful, and other similar data seem to interest readers more.

Just to make it clear, the data itself is usually objective. Subjectivity and judgment come into play when conflicting data exist, such as different numbers from credible sources of a satellite’s mass or identifying whether a rocket is launched in the service of a military or commercial mission (sometimes not so obvious for launches from China). Even who launches a rocket can become a judgment exercise because of translation challenges.

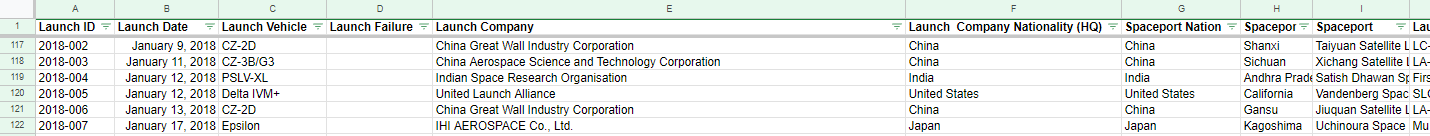

These are my considerations when I create spreadsheets for my writing and business intelligence charts. I decide what’s potentially meaningful and collect the data to help me. The resulting spreadsheet looks like this (apologies for the small text):

It’s part of a slew of spreadsheets I use for the Global Space Activity Dashboards.

The latest Starship launch helps demonstrate my process. A lot of information is vomited to the world by the company, its CEO, and fans–some might be true. We know who is launching Starship, where it is launching from, that it has zero payloads, that it is using a suborbital trajectory, etc. I’ve collected and entered its information in a few spreadsheets before its latest launch. Prior to using any of that data, I need to define Starship in its latest iteration. Figuring that definition out determines whether I should count it as an orbital launch. Test launches of different rockets have been conducted and counted before. But, those typically deployed something into orbit.

The Starship test didn’t do that. An honest look at the mission profile shows it followed a suborbital path (and I don’t cover sounding rockets, no matter how bigly they are). Even sounding rockets deploy something. At the same time, Starship is the center of much attention. It might be the future of launch. While the rocket hasn’t deployed anything that’s orbited the Earth a single time, its last two tests suggest it could. That’s when I again fall back on that whole “judgment” thing. I included the latest Starship test in the Global Space Activity data for those last three reasons.

My Process, My Windmills

Of course, if it had failed, I would have marked it as a launch failure and moved on. All the data I collect becomes useful to me, even failure data. Sometimes, it takes imagination. However, my work also requires judgment, which stems from experience, observation, creativity, and thoughtfulness. People might be surprised at how much judgment comes into play concerning collecting data. But that’s my process.

I wouldn’t be surprised if I’m missing some critical data. However, part of being a good market research analyst is constantly evaluating what works and what doesn’t (this includes tools and reader reactions), refining data collection, and adding to it (or paring it down) as necessary. The industry is growing and changing so much that not adjusting to those changes risks making observations and analyses irrelevant.

As an aside, readers hopefully learned that there are many free tools online. Remember everything I listed in this article? I use a lot more than that, and most of it is free, such as Google Looker Studio, interviewing software like Meet or Teams, writing tools such as Docs, Word, or LibreOffice, and spreadsheet software such as Excel and Sheets. Even webpage hosting and newsletter emailing have a few free options (like Substack). For that reader wishing to start something online, there’s probably a free tool available.

What are you waiting for? Start your own process.

If you liked this analysis (or any others from Ill-Defined Space), I appreciate any donations (I like taking my family out every now and then). For the subscribers who have donated—THANK YOU from me and my family!!