Revisiting 2023 Space Industry Activities

Hard to believe that another year has gone by. Some space activity revisiting is in order.

The next few weeks after I post this revisit are holiday-filled and busy with good things for me, such as visiting with relatives and friends. I will even be baking cookies! So, no posts for the next two weeks. Although, if something catches my eye, I reserve the right to write it up for the second week.

For my 1300+ subscribers, thank you for taking the time out of your busy days to read my thoughts. I am humbled by your commitment and hope I’ve provided some good reading for you. Have a great holiday and New Year!

On to my last article for the year…

Gosh!

As with 2022, 2023 has been chock-full of space industry activities. From launches to the various reports, A LOT has happened. However, I’m not going to cover it all. Instead, I’m revisiting a few of the things I covered during the year that are relevant today and seem to be relevant, at least for 2024 (in some cases, hopefully longer).

Although this revisit is posted before the year’s end, there are some apparent observations to get out of the way. And, while the year isn’t over, the numbers are so overwhelming that whatever happens in the next few days will have a negligible impact. However, charts in this article will be available with updated data at the year's end.

The space industry broke all sorts of records. There will probably be more than 200 successful launches in 2023. Nearly 2,800 spacecraft will have been deployed. Those spacecraft masses mean over 1,400 metric tons will have been deployed into space.

Of course, a large part is from SpaceX’s Starlink deployments (which will be a different article).

Activities

Global space launch industry frailty

Amazon Kuiper

China’s space activities

Reusability

Global Space Launch Industry Frailty

Specifically, the following highlights the dangers of space launch service frailty from any launch nation EXCEPT FOR China.

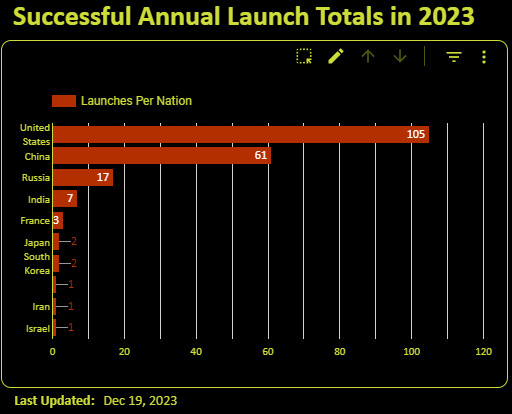

Sure, rockets from U.S. launch services make up more than half of all projected 200+ launches in 2023, but so far, SpaceX has taken nearly 88% of all U.S.-operated launches. The company looks to be on track for launching ~47% of the world’s launches during 2023. China’s launch services will take the second-highest share of global launches–on track for ~30%.

As a second data point, 52 nations have satellite operators who have already deployed spacecraft in 2023. Forty-two were deployed from a Falcon 9–nearly 81% of nations with space operators in 2023. On the other hand, China’s diverse launch services deployed spacecraft from two nations: China and Egypt. Over half of the world’s satellite operators relied on SpaceX’s Falcon 9 to deploy spacecraft in 2023. Nearly half of those satellite operators, 60, could be considered relatively new players in space operations.

Those startups were attracted to SpaceX’s low per-kilogram pricing offered in its Smallsat Rideshare program. However, the lack of any alternative to the Falcon 9 surely had something to do with their selection, too. Not only, then, are most of the globe’s space operators relying on SpaceX to get to space, but the most vulnerable–the startups–are also reliant on the company.

This reliance means that if something were to happen to SpaceX, the U.S., EU, commercial companies worldwide, and others wouldn’t be able to deploy their spacecraft until Arianespace, Blue Origin, and ULA finally do what they keep announcing they’ll do. And if they eventually launch, the startups that SpaceX caters to would still face dire straits, as those three companies aren’t catering to them.

SpaceX is strong, but the launch market is weak. It can be strengthened (I have a few ideas about that).

Amazon Kuiper

Amazon Kuiper is slowly acknowledging that the weakness in the launch market is taking longer than anticipated. Part of that acknowledgment came in the form of a contract with SpaceX for three launches.

When looking back at Kuiper’s contracts, it’s entirely possible the company saw the launch market weakness early on. Maybe it believed it could accelerate rocket development efforts by providing cash infusions using contracts with Arianespace, Blue Origin, and ULA. It had time since its satellites weren’t ready for deployment when the contract announcements were made, and each company seemed to be promising a new rocket launch soon.

But those contracts' initial rule of thumb seems to have been “anyone but SpaceX.” And if the choice was between ghost rockets from those other companies or SpaceX, then the companies building the ghost rockets got the contracts.

However, Kuiper seems ready to deploy satellites, but the ghost rockets are still just figments in the air, except for ULA’s single Vulcan. Kuiper has a deadline to deploy at least 1,618 satellites by mid-2026, 2.5 years from January 1, 2024. To meet that deadline, the company must deploy 54 satellites per month (from Jan 1), meaning it must manufacture at least two satellites daily. If it can do that, Kuiper relies on three companies with three brand-new, untested rockets, except for the three SpaceX launches.

Those companies must not just launch those new rockets but build them at rates they never have in the past. The processes to do so will be challenging, which will lead to slowdowns. The launch crews will also be adapting to changes.

Again, all of those realities, and more, will cause Kuiper to commit to more SpaceX contracts, which might constrain launch supply. The temptation to behave as a monopolist may be too much for SpaceX to resist. Especially if Kuiper actually meets its deadline and becomes a competitor to SpaceX’s Starlink. The launch company could deliberately schedule launches that are much later than Kuiper desires, but before SpaceX’s competitors start launching their new rockets.

Based on its test deployments and recent comments, it does appear as if Kuiper will become that competitor.

China’s Space Activities

China is…odd. But odd is okay. Odd is different.

It’s odd because its space-related companies and organizations are extremely active. The nation hosts many types of satellite manufacturers and operators, and many launch services to deploy them. The result is that China’s companies have the second-largest share of satellite deployments and launches in 2023. Despite that share, they have a negligible impact on the overall space economy and its various markets, space activities, and launches. Maybe they have terrible business development managers?

China has the most diverse launch market on the planet, but in 2023, those launch services catered only to Chinese customers (or Egypt–but that’s it). But even with that focused customer base, China’s launch providers launched over 30% of all successful 200+ launches in 2023.

If China’s launch industry were compared to the U.S. in bodybuilding terms, the U.S. would show up as a runt with a huge, overdeveloped arm. China would win the competition because of its symmetrical and comprehensive development. However, balanced development only goes so far.

Most of the rockets from China’s launch services cannot lift at least 4,500 kilograms into low Earth orbit—quite a few focus on launching smallsats. And the rockets that can lift an equivalent Falcon 9 payload mass can’t launch nearly as quickly as that SpaceX rocket. So, China’s launch services present a more pleasing, perhaps healthier-seeming, industry. But they can’t keep up with the runt with the overdeveloped arm–because it is so strong, capable of lifting more.

That mass capability imbalance shows in the number and mass of spacecraft deployed. By the end of 2023, China’s launch services deployed nearly 200 spacecraft in orbit. SpaceX managed to deploy 11X that number in the same year. China's launchers lifted an estimated 106,000 kg of mass into space for 2023. However, there were five months in 2023 when SpaceX, using the Falcon 9 alone, exceeded that total each month. If SpaceX launches a few more Falcon 9s laden with Starlinks before year’s end, it will have deployed an estimated 1,200,000 kg of mass to orbit.

As noted earlier, however, the U.S. dependence on that overdeveloped arm (SpaceX) is creating launch service frailty for that nation. There’s no equivalent other arm to take over should something happen.

Despite the imbalance, many Chinese companies are seeking to out-SpaceX SpaceX. They want to deploy thousands of internet relay satellites (even as they deploy hundreds of Earth observation satellites). They are developing reusable rockets. And considering how active and driven these companies appear in their pursuit to dominate SpaceX, they might, at the very least, bring more to the market than SpaceX’s Western competitors.

That would be especially true, if and when China’s space companies start entering the world’s space stage.

Reusability

Reusable rockets comprised the majority of rockets launched in 2023 (90+ out of 200+ successful launches). Even if competitors met their annual launch averages of 10 to 12, reusable rockets would have dominated the launch services. That fact alone highlights one of the strengths of reusable rockets. If future and current competitors haven’t seriously considered the question, they aren’t paying attention. Of course, only one company–SpaceX- routinely launched reusable rockets.

Even before SpaceX began to implement the reusability of the Falcon 9’s first stage, its rivals questioned the notion of whether the idea made business sense. The first successful launch and landing of a Falcon 9 occurred almost eight years ago. During that time, SpaceX’s competitors have yet to satisfactorily answer their questions about rocket reusability, while SpaceX keeps answering why as it eats their lunches.

Some of the companies have plans for half-hearted reusability implementations, demonstrating a fundamental misunderstanding of reusability’s strengths. Only a few companies in China appear to be taking the idea seriously. They are making strides in reusable rocket development that put U.S. commercial entrepreneurial efforts to shame. Rocket Lab also seems to be seriously pursuing reusability but isn’t as far along as the companies in China.

For those wondering, while reusability saves some money during launch, there are other, more important considerations. First, a company with reusable rockets doesn’t have to anticipate the future number of possible customers and then build rockets accordingly. It already has rockets readily available.

That access means a company with reusable rockets can aggressively pursue launch customers without worrying about overcommitting rockets. It can seek out customers who made no sense in the past to chase because they are paying for a part of the rocket instead of the whole thing. This customer expansion is a reason why SpaceX can offer its Transporter missions.

Reusability also gives a degree of flexibility and certainty to customers. Flexible, in that SpaceX can add missions to its launch manifest quickly. Certain because the customers have seen how used Falcon 9s have performed similar missions–seemingly without a hiccup. There is some truth and comfort to a rocket being “flight-proven.”

Is there a business case for reusable rockets? Yes, based on what we’re seeing with just one active reusable orbital rocket. Does that mean all competitors should develop reusable rockets? No–that way leads to fads. And a company might come up with a novel and better way to achieve what SpaceX has achieved. But for any company in or entering the launch business–it is important enough for research and consideration.

That’s enough for the revisits this year, I think.

Curious about the graphs? Just jump over to the Global Space Activity Dashboards to see updated versions of them and more.

Curious about the images? Head over to Microsoft Bing’s Image Creator and try your hand a creating a space masterpiece (or space oddity).

If you liked this analysis (or any others from Ill-Defined Space), any donations are appreciated. For the subscribers who have donated—THANK YOU!!

I continue to be surprised by the almost complete collapse of ULA launches. It was not long ago that SpaceX was suing to get a chance for the USA DoD launch contracts. I understand that ULA stopped buying rocket motors from the Russians after the 2014 invasion of Ukraine. That was a decade ago. It sure did not take 10 years to make new rockets in the 1960’s.