Focus On: ULA’s Challenges, Part 2

The second part of an earnest look at ULA’s challenges. And SpaceX released a Starship "flight plan," which is interesting, but aspirational.

ULA launched SBIRS GEO-5 a few days ago. The company posted a video of satellite separation from the rocket’s upper stage on Twitter here. I am a little surprised ULA posted it. Tory Bruno posted a slow-motion close-up of the launch here.

I ended the first part of this analysis by asking whether there was a market incentive for ULA to invest in facilities, people, and training to launch at least 13 to 15 rockets a year.

Working Harder for Less

In the last analysis, the data indicated that ULA was making a bit of hay while not launching as often as it had in the past. In the meantime, SpaceX appears to be making plenty of money (but not quite as much as ULA--nearly 25% less).

But SpaceX is launching a lot more than ULA, 50 to ULA’s 13 over two years. Subtracting the 23 Starlink-dedicated launches makes the comparison a bit more apples-to-apples. Even then, SpaceX launched at least twice as often as ULA and still fell 25% shy of the total that ULA’s customers paid during the same time.

Since ULA’s less active launch schedule still ends up providing significant amounts of cash to the company, does it make sense for ULA to chase SpaceX’s launch rate? Is there an incentive for it to do so? After all, the estimates indicate ULA is doing quite well.

Knowingly Painting Into a Corner

If the company relied only on internal motivations, then probably not. ULA had a headstart on any U.S. competitor. It was the sole launch provider for expensive DoD and NASA missions, commanding increasing premiums for its services. It could have innovated its launch systems and business model while conducting government launches but didn’t. It received money and the opportunity to manufacture rocket engines which it never manufactured. Instead, ULA asked for permission to buy more Russian rocket engines.

When it had no competition, ULA always chose the blue pill. There’s no reason to think it wouldn’t choose the same now if circumstances hadn’t changed. External motivations, however, do provide ULA some incentives for change, forcing it to at least contemplate taking the red pill.

The rise of SpaceX as a competitor certainly changed ULA, however much the company may deny it. As SpaceX sued the U.S. Air Force to get a piece of the Evolved Expendable Launch Vehicle (EELV) contracts, ULA started to design a new rocket, one not dependent on Russian engines. The new design was announced right before the USAF certified SpaceX’s Falcon 9 for EELV (which eventually morphed to NSSL (National Security Space Launch)). ULA started laying off nearly a quarter of its workforce a year after that. ULA is also partnered with Blue Origin to gain access to an engine for its new rocket, the Vulcan.

And while the DoD hasn’t admitted it, SpaceX is helping the U.S. military come to terms with the concept that reliable launch services can be had at lower prices. That concept at least appears to be the reason for the SBIRS GEO-5 launch award cost. The DoD’s awarding of lower-priced NSSL contracts to ULA (examined in part 1) impacts the company’s business (even though the per-launch awards are still higher than those awarded to SpaceX). The last two NSSL awards to ULA yield an average of $141 million per ULA launch. That average, down from $382 million, means the company needs to step up the rate of launches it conducts each year--if it wants to stay at the revenue levels it’s historically enjoyed.

Considering the external realities and motivations, ULA doesn’t appear to have a choice: it must change. Can the company get out of the corner it’s painting itself into? Or is blue too soothing of a color?

Transitioning from Government to Affordable Market-pricing

In the first analysis, I noted that ULA needs to do these things if it wants to remain relevant as a launch service provider:

Launch significantly more per year

Court commercial customers

Court international customers

Lower prices

With data indicating that ULA needs to launch more rockets per year, how does the company achieve that goal? I’ll begin with a few guesses and observations.

I believe ULA’s people have tried selling the company’s launch services to businesses outside of the civil and military realms. But, using ULA’s rockets is probably a difficult sell to any company that doesn’t have money coming out of its ears.

The company’s service, even with its current lower pricing, is still too expensive. Which is probably why Project Kuiper contracted with ULA for nine launches--using its Atlas 5 rocket? ULA is the only viable U.S. company for Project Kuiper to turn to, with the benefit of not contributing to the bottom-line of a LEO broadband competitor. Aside from that Bezos-backed project, as seen in the previous analysis, ULA is strictly catering to taxpayer-funded missions.

All of the above means that ULA is focused on U.S. government business because the customers from the USG aren’t as cost-constrained. And it’s focused on USG business because commercial companies are choosing much-less-expensive launch options.

The strategy for change may prove to be comically cyclical. The company needs to aggressively expand from its government focus and pursue businesses (which it is probably trying to do, as shown with the Project Kuiper contract). But to get businesses interested, it needs to lower launch pricing. It could probably adjust pricing to be above SpaceX’s “internet pricing” and still gain commercial customers. But to lower launch pricing while still generating revenue requires gaining more customers.

To be clear, ULA is probably operating reasonably close to the bone with its current rockets, meaning that ULA can’t lower the launch prices of its current inventory of rockets much more than its SBIRS GEO-5 launch contract. It can’t get cut into its workforce without hurting itself. And it’s not wise to do so when the company decides to ramp up operations. The Vulcan may also provide some relief, as it will be more automated, requiring fewer support crews. But the Vulcan hasn’t launched yet.

But there are other ways to help ULA out of the corner, to be laid out next week.

Miles to go Before the Flight

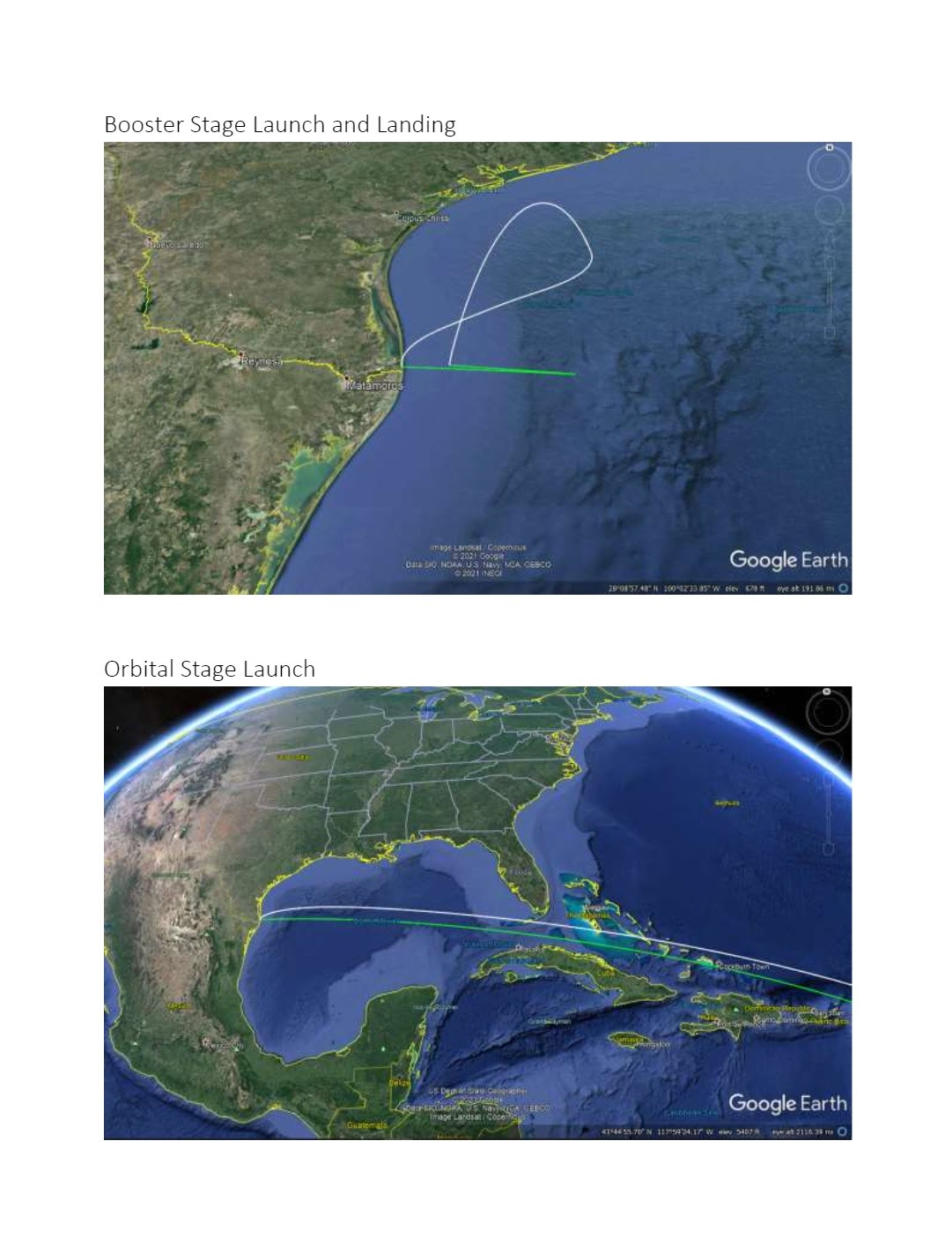

SpaceX provided a Starship “flight plan” to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) last week. Instead of the “usual” test of powering the Starship second stage to 10 kilometers and then bring it down for a successful landing, the company will launch Starship east from Boca Chica, Texas, rise above the Florida Straits to orbit, then come down about 100 kilometers northwest of Kauai. A few drawings of the flight plan are in the snip below:

Before anyone gets too excited, a few things need to happen before this flight plan ever becomes a reality.

Starship launches and landings need refinement. The company will also need to test it with more engines. Starship will also need to test the heat shield tiles (an altitude of 10 km does not do this) before the flight. The company has been installing little patches of heat shield tiles on the prototype Starships (probably testing mount methods).

The Super Heavy booster, which will loft the Starship into orbit, has yet to be launched. It’s still in assembly. Super Heavy itself is likely the more straightforward piece of the system, as it will face similar flight conditions SpaceX’s Falcon 9 boosters are going through every launch (and they appear to be landing much more reliably). The Super Heavy will contain many more Raptor engines that will need to be tested in specific configurations.

At least the Super Heavy would have the less complicated role, except Musk has decided the Super Heavy’s launch tower will also “catch” Super Heavy instead of the first stage using the ultra-cool-looking landing legs. The first few tests of that system are going to be spectacular. Musk rationalized the change as necessary for quick-turnaround reuse of the booster. It’s less time-consuming to have it return to the launch pad under its power. And, yes, there are mass savings with no legs on the first stage.

The real unknown is just how quickly SpaceX can go through each test to get to the point of testing the system using that flight plan. The company has been very speedy so far. Even so, while it’s interesting to see a rudimentary flight plan, SpaceX isn’t afraid to change things. The flight plan could be one of those things that change.